The Animation of Disney's 'Frozen': Striving to Capture the Performance

Underneath all the visual design, digital effects and filmmaking technology lies the artistry of the animated performance.

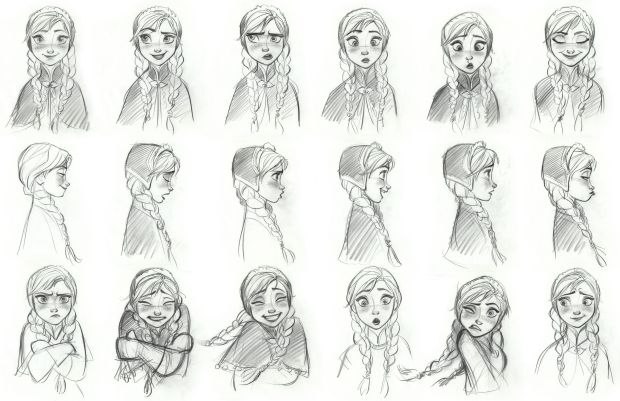

Anna, from Disney's upcoming feature film Frozen. Except where noted, all images © 2013 Disney. All Rights Reserved.

Understandably, access to the inner workings of a $150 million animated feature film production is kept tightly under wraps. From story, to design to the production process, information about a film is fiercely guarded, doled out in drips and drabs to the press as well as to audiences through tightly controlled PR and marketing machines. Anticipation amongst fans and the media starts running higher as a film nears completion.

Consequently, as the release date approaches and the studios begin to grant access, we all jostle for position to find out as much as possible. There is no shortage of fascinating topics and investigative angles to dig into. As animated features have become so unbelievably complicated, so has the business of learning about and reporting on how the films are made, the intricacies of production and the talented people involved at every level. It’s easy to get lost in the complexities of a big studio animated feature film production. Voice talent, visual development and previs, art direction, costume design, character design, story development, look development, rigging, lighting, layout, effects and simulations, the list is endless, as is the list of inherently interesting topics for discussion in each and every area. Getting an intimate look under the hood of a film like Disney’s latest animated feature Frozen is, for anyone even remotely interested in animation, a real treat. A dizzying treat. Where do you even start?

The recent Frozen press day at Disney Feature Animation is a perfect example. Presentations by numerous production teams. Interviews with co-directors Chris Buck and Jennifer Lee, producer Peter del Vecho, art director Michael Giaimo and his visual development team, Frank Hanner and the character TD team, Marlon West and the fx animation team. Each fascinating, each worthy of time in the spotlight, all with great stories and all vital to the success of the production.

However, when you wade past the snow and ice crystal sims, the studies of how heavy cloth skirts move in deep snow and how some frame renders took over 5 days, the numerous teams of artists, piles of artwork, rows of workstations, racks of servers and conveniently located breakfast cereal snack stations, you eventually get to the heart of the production, what links Frozen to every animated feature the studio has made since the release of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs in 1937 – the performance. When you talk about the magic of animation, the very essence of how and why these films have captured the hearts of audiences dating back 75 years, it’s not the lighting, the cloth sims or the beautifully designed castles. It’s the performance. It’s the animation. That’s what captures audiences and draws them into the story.

Head of Animation Lino DiSalvo, Animation Supervisor Wayne Unten and Animation Supervisor Becky Bresee.

Spending just a few minutes with Frozen’s head of animation Lino DiSalvo and two of his senior animation supervisors Wayne Unten and Becky Bresee, you realize that first and foremost, they live and breathe performance. Their passion about this film is contagious. Their job is to bring feeling, emotion and energy to the film’s characters, to help shape them and flesh out just exactly who they really are. They create the performance. As DiSalvo puts it, “Our ultimate goal is doing these characters justice, getting a team of 60 animators to push for believable performances with honest and truthful acting.”

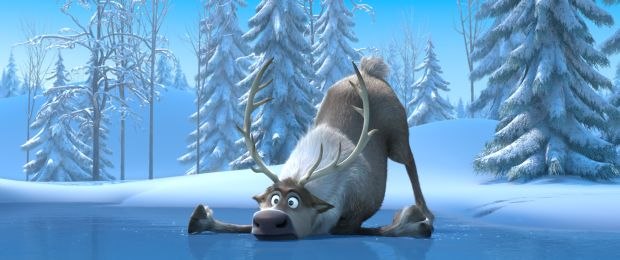

For the animators, the process began years earlier with the help of an acting coach, going over every single character in the story, discovering who they are, their stories, working with the voice actors, studying how they moved, how they breathed, the tension in their faces when they spoke and sang. Reference trips were taken to the snowy plains of Wyoming and the icy fjords of Norway. A live reindeer was brought into the studio. Soon, animators learned they scratch their heads with their hind legs, just like a dog. Endless tasks involving endless details from over two years of preproduction that had to be done before animation could even begin.

Then animation tests were done to visualize what the main characters “could” be, defining a type of “shape language” that impacted the final CG model. 2D sketches, drawings, model sheets and volumes of other artwork were integrated with the latest CG tools to bring the characters to life.

Bresee’s process typified the all-consuming nature of production. Her work on Anna started with instructions from the directors, what they were looking for in each shot. With a computer-mounted camera in her office, she filmed herself acting out each of her scenes dozens of time, continually refining her performance. She’s done this on every movie she’s worked on – she filmed her dog for Bolt, her husband for Tangled, even her daughter for scenes in Frozen featuring little girls. According to Bresee, “I’m looking at poses. I’m looking at expressions. I’m looking at the timing of certain things I do with my hands. For close-ups, I’m looking for things you do with your brows, even little perky things you’re doing with your mouth. I’m trying to grab something that makes it feel real, feel believable.”

Like DiSalvo and Unten, she started by first creating key poses, putting them into what’s called a “blocking pass,” done to get something in front of the directors as quickly as possible. Iterative blocking passes were done to get buy-off from the directors before the much more involved rough animation began.

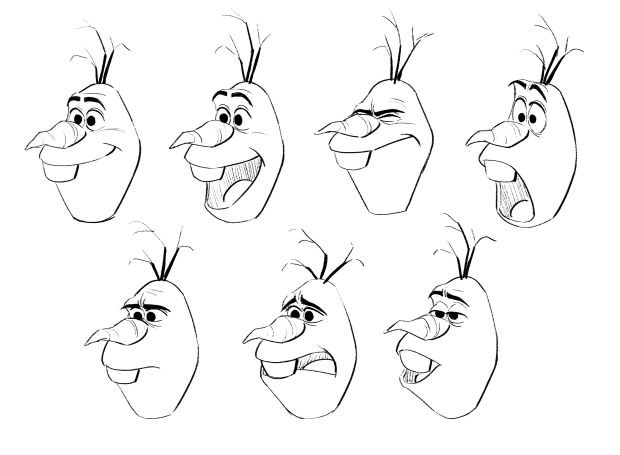

For the comedic character of Olaf, a snowman, animation tests helped determine his overall design. His arms are made of sticks. How should his arms move? If he has no elbows, how does he scratch his head? How do the pieces of his body come apart? How does he move? How does he think?

As co-director Chris Buck explained, “For the animation team, Olaf was like a giant toy box. He’s made up of three balls of snow that can break apart and come together in different ways. His eyes can move around, his nose can slide in and out and off. His stick arms came off. Animators could do anything with him.” Co-director Jennifer Lee pointed out that as far as Olaf’s performance, “Olaf went through many iterations in development. He had so much potential. We found him as soon as we asked, ‘How does a snowman think?’”

DiSalvo used hand-drawn 2D for many of the blocking passes on Olaf. As he explained, “I had never animated Olaf. I had a limited amount of time, I wasn’t yet familiar with the rig, so I just did it by hand. Later, I just matched up the CG to what I’d done hand-drawn. No matter what tool you use – paintbrush, pencil, charcoal, CG – the end result is always that appeal, the entertainment, the performance.”

Matching the performance to the story is difficult, as an animator’s idea of what the acting should be doesn’t always mesh with the director’s vision for the scene. Part of DiSalvo’s job as head of animation was keeping an eye on such details. “Sometimes you have to make hard choices. A shot looks good, but is it the right ‘thing?’ The animation looks beautiful, but was that really supposed to be a funny moment? What if we just wait and get the payoff a little bit later? Making those choices is like conducting. You have such talented artists. The conductor is uniquely in tune to those little accents, those notes, those beats and where to put them.”

On Tangled, DiSalvo learned from one of the best, the now retired Glen Keane, how to push the performance as far as possible. The iterative process of animating, reviewing in dailies, making notes then making changes, is designed to get the best performance you can. On Frozen, like Keane on Tangled, DiSalvo had the responsibility of helping his animators push the performance. He described the thinking. “Is it authentic? Is it genuine? Do you buy it? It’s about giving notes in dailies and seeing shots coming back looking much better. I’m trying to do exactly what Glen [Keane] did for me early on. We’d take a shot that was really good. He’d ask, ‘Is the subtext real? Do you have too many poses?’ We keep echoing that stuff. Passing the baton. Now I’ve got it. The next show already is picking up from where I left off. What’s great for me is that now, instead of being able to affect five shots, I’m affecting the whole film. I tell Chris and Jenn all the time that this is the highlight of my career.”

He continued, “In Tangled, we broke a wall down. Acting-wise, having Glen there to push you to find the truth in what you’re caricaturing, we all learned that on the film. I started Frozen with that knowledge. I learned that all on Tangled. But now, it’s a finely sharpened tool instead of a blunt instrument. When Idina Menzel [the voice of Elsa] came in and we showed her two sequences in particular, she paid us the ultimate compliment. She said, ‘What you guys are doing here, some of the great actors, I don’t see it in their performance.’ She noticed little furrowed brows, wrinkles, eye tension, pulsation in the lips, the breathing. Then her husband [actor] Taye Diggs told us he kept getting wrapped up and lost in the characters’ eyes. It was so cool because that’s exactly what we were trying to do. Being told we’re creating performances that you often don’t get from live action. That is the ultimate compliment for an animator.”

And from the looks of the 25 minutes of finished animation shown to the assembled audience during that press day, it’s a compliment well deserved. Frozen opens in theatres across the U.S. this coming November 27.

--

Dan Sarto is the editor-in-chief and publisher of Animation World Network.

No comments:

Post a Comment